Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered weak and weary…

Ever wondered why some poetry sounds so good when you speak it out loud? How it contains its own rhythm that you can’t help but fall into? There’s a word for that. Poetic meter*.

This article started life as an essay on meter and how to write in it. But seeing as I got bored writing it, I figure it wouldn’t have enticed my readers to stick around reading it. And I am married to a web analyst who notices things like my website’s performance. So we’re going to try something snappier; more fun and more visual.

Off on the right foot

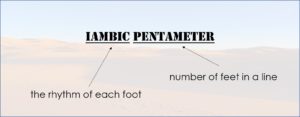

The rhythm and length of lines in poetry is described using words like iambic pentameter and dactylic tetrameter. The -meter bit refers to how many feet there are in a line. The first bit refers to the rhythm of those feet. What’s a foot?

Feet are the sets of two or three syllables that each have the same rhythm (for the most part). Here I’ve chopped up Shakespeare’s Sonnet 18 into its feet. There are five feet per line, so this in pentameter. Speak it out loud – the rhythm goes du-DUM da-DUM da-DUM da-DUM da-DUM. When a foot has an unstressed syllable followed by a stressed one – when it goes da-DUM – that’s called an iamb. So this is written in iambic pentameter.

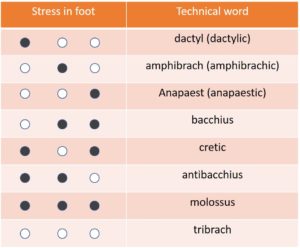

Of course, you don’t have to have five feet in a line. And those feet don’t have to go da-DUM.

You can have as many feet as you want

Above, my personal favourite poem: Edgar Allan Poe’s gothic masterpiece The Raven.

This has eight feet in a line, and those feet go DA-dum, DA-dum, DA-dum. This is written in trochaic octameter.

You’ll notice we’ve made a couple more friends there to go with iambic and trochaic. It’s pretty hard to write a line with all unstressed words; also stressing all of them sounds unnatural and will give you a headache. So spondee and pyrrhic are more like variations on lines written in iambic and an trochaic. For example, a line of iambic heptameter might switch some syllables around for effect and consequently include a spondee or pyrrhic.

Iambic pentameter is what a lot of Shakespeare is written in. It sounds very regal and stately. Trochaic meters tend to sound a bit punchier since the stress comes first, hammering its way forward.

You don’t need two syllables per foot you know. You can have three if you want.

There’s more than one rhythm for poetry

The drummer in me wants to draw a parallel here to a triplet-based rhythm, but I realise that’s a fairly niche comparison. Nevertheless, these rhythms are all based around feet of three syllables. For example…

This is from The Lost Leader by Robert Browning, another of my favourite poets. It’s written in – did you get it? – dactylic tetrameter.

I really like the three-syllable meters. They have a waltzy kind of motion that sounds good in a folksy tale, or matched to a poem about rolling waves. Because you’re dealing with three syllables per foot rather than two, your lines end up longer and can accommodate longer words. You’ll notice that Browning left off a few syllables after starting the last foot of each line. It sounds very natural; it lends a pause between lines. There’s no rule against not filling every syllable in a foot; there are no rules in poetry. But sticking to a few guidelines does make those little rule-breakings all the more effective when you do them.

Poems written in three-syllable feet can get quite long. There’s more syllables in one line of dactylic tetrameter than in a line of iambic pentameter, even though there are fewer feet. I once wrote a poem in dactylic hexameter – there were six feet per line, six lines per stanza and six stanzas in total. Well, it was inevitable I’d write a poem inspired by the number of the beast.

Anyone can write in poetic meter

That about wraps up my introduction poetic meter. Of course a poem doesn’t have to be in meter (if it isn’t, it’s probably in free verse) and, even if it is in meter, it doesn’t have to rhyme (unrhyming iambic pentameter is called blank verse). But some poetic forms, like sonnets and villanelles, are often written in a certain kind of meter. Poetic forms? We’ll take a look at those next time.

*I will be spelling it meter throughout this post. Sources differ on whether it should be meter or metre; American English certainly endorses meter but English English leans more towards metre. What with pentameter being spelled the way it is, I’ll be standardising to meter across the board.