If you look up a list of the scariest horror films ever made, William Friedkin’s 1973 movie The Exorcist will most likely be on there. And deservedly so: it’s an absolute shocker of a film, full of horrifying imagery and terrifying implication. The Exorcist is more famous as a film than as a book, even though it’s based on an excellent novel by William Peter Blatty. This Halloween I treated myself to reading the book and, as a writer, I learned a lot from it.

The premise (no spoilers!)

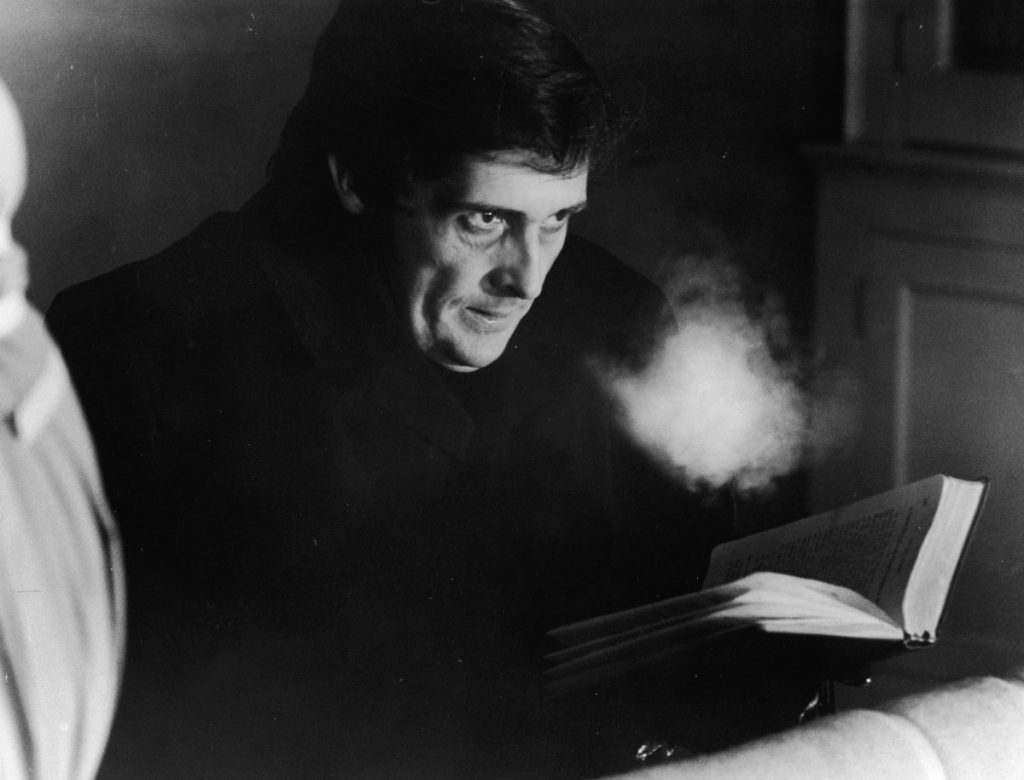

The Exorcist concerns the deterioration of twelve-year-old Regan, the daughter of film star Chris MacNeil. Initially, Regan’s bizarre behaviour and sickness is thought to be symptomatic of psychological illness. But the extreme and often blasphemous nature of her affliction leads her mother to believe Regan may have been possessed by a demon. It falls to Father Karras, a local Jesuit priest and psychiatrist, to investigate whether Regan is possessed, and to obtain authorisation to perform the titular exorcism.

How to write a scary book

The Exorcist is frequently named as terrifying film, but rarely do books get the same kind of recognition for petrifying their readers. Perhaps it’s because books must rely on the imagination and interaction of their readers to conjure terror. Maybe it’s because it’s easier to sustain the effect of terror over a two-hour movie than it is in a book that might be read over the course of a week or more. In any case, it’s accepted that a book provides a different form of horror than a film; a slow burning, more cerebral scare.

Horror is real – and scientifically proven

Blatty’s The Exorcist is a scary book. While it concerns supernatural possession, it is never framed as a fantasy. It takes place in the real world and, as such, its horrors seem possible and tangible. This is not escapism but a harrowing suggestion of what the effects of hell on earth could be.

Throughout the book, protagonist Father Karras seeks scientific reasons for Regan’s behaviour. He researches examples of telekinesis and telepathy, schizophrenia and psychosis. That he can scientifically explain phenomena as varied as the girl’s understanding of Latin or the handwriting that appears in her skin grounds the book in realism. What’s more, it acknowledges the potential for horror to be found in the human condition, without any supernatural influence. What could be scarier than what our minds and bodies are already capable of?

Taboo voodoo

But bringing such horror into a real-life framework could risk reducing its effect – after all, if it isn’t extraordinary, it might not be interesting. But The Exorcist is riddled with horrifying imagery that grabs and holds the attention. The book is consistently shocking as it confronts the taboo – blasphemy, sexual corruption, scatological depictions – all with reference to its central character, the pre-teen Regan. The Exorcist is obscene, but justified by its context. It’s horrifying, and it’s the escalating horrors it presents that shock the reader and keep them pinned, whilst the momentum of the story continues, and its realism keeps things believable and therefore scary.

Such an analysis might make the book sound exploitative, but The Exorcist never seems pulpy or sensational. Blatty’s prose is intelligent; literary and modern. He does not linger over descriptions of horror, but relays them efficiently, allowing the nature of the things he describes to implant in the reader’s mind. We, as the reader, do the heavy lifting with our imaginations.

Characters feel terror, and readers feel what characters do

Blatty is a dab hand at providing enough detail to prompt our imaginations, and utilises those same skills in drawing his characters, allowing us to form our own pictures of the cast. Moreover, Blatty is a master of dialogue. Some of the most gripping scenes in the book are the exchanges between Father Karras and the demon/Regan: Karras trying to learn more about what might be possessing Regan, and that very demon toying, abusing and insulting him. But some of the cleverest dialogue comes from a secondary character, Detective Kinderman, who believes the MacNeil household is linked to a horrific death that happens just outside their door.

Kinderman’s speech – interspersed with asthmatic wheezes – is laced with the bumbling cadence of real speech. Kinderman himself refers to his ‘schmaltz’ – his blustery way of speaking. Different characters react in different ways to this dialogue – Chris MacNeil is taken in by it and questions how Kinderman ever made detective, but psychiatrist Father Karras cuts through the schmaltz and speaks to the intelligent man behind the bluster. Characters are our windows into stories; the avatars we find ourselves possessing. Such interplay between characters engrosses us and plants us in the story, especially when their mannerisms and speech sound so authentic. We feel the feelings they do; we are scared or horrified along with them.

Good writing compels you

The Exorcist is one of the scariest books I’ve ever read. Sure, the things that happen in the book are horrifying, but it’s the immersive nature of the book that allows the horror to connect with its reader. A book is only paper (or a tablet screen); it’s the words inside and our understanding of them as the reader that creates the terror. William Peter Blatty has created a realistic world for us to inhabit, then traps us in it with gripping prose and subjects us to the traumas of his story. He sees the length of time it takes to read a book not as a challenge but as an opportunity. He doesn’t present us with a two-hour movie’s jump scares but instead creates a story of escalating, taboo-facing horror that we dare not look away from. For a writer of horror, there’s nothing more inspiring than that.

Completely agree that our minds can conjure up much scarier stuff than on the screen. We all know the power of a ‘can’t put down book’ and sometimes you have to save your muchly anticipated ones for a long reading session so you can get thoroughly absorbed!