Earlier this week I listened to Red Barchetta by Rush. Haven’t heard it? Give it a listen. Red Barchetta is a narrative song about a future in which a ‘Motor Law’ bans many vehicles, such as everyday cars. Every week, the story’s protagonist sneaks out to his uncle’s old farm and takes an old sports car, a Red Barchetta, for a spin on the country roads. The music ramps up in intensity as the car picks up speed, and cymbals crash in time with guitar crunches as the Barchetta is spotted and chased by modern air cars. This would make a brilliant story, I think to myself. But then, it’s already a story – there are different mediums of fiction. Red Barchetta is a story written in sound instead of sentences.

This got me thinking. Does a story have an optimum medium, a format that best suits it? Take Red Barchetta. Its premise is not so dissimilar to Ray Bradbury’s beautifully written Farenheit 451, and that works brilliantly as a novel. But would fleshing out Red Barchetta into a novella actually improve it?

Music and lyrics

Part of the fun of Rush songs is in matching the music to the plot; hearing how the band interpret narrative and apply rock riffs to it. The lyrics conform to a recurring melody but are vividly drawn ; they are stream-of-consciousness, working in tandem with the music to paint a full picture of emotion and effect that words cannot alone portray. Could it work as a short story? Sure. But it would be a different experience. The magic of music is that it isn’t quantifiable – it’s an abstract. There’s no physical reason that a minor chord is ‘sad’, or a major one ‘happy’; we just interpret it that way. Music works by implying mood and as such is open to interpretation; everyone will connect to it differently and that makes it a very subjective and personal medium.

Written stories are frequently more explicit – they don’t have the luxury of another layer of communication, and often have to explain how characters are feeling in quantifiable terms (“Neil was excited”) rather than letting a more abstract or implicative element guide the reader’s experience. Then again, isn’t the secret of writing to transcend the countable nature of words? To compose words and sentences in such a manner as to communicate the abstract – to compel the reader to feel something inside despite the fact that, physically speaking, all they’re doing is holding a piece of processed tree with ink stains on it?

Video killed the literary star

Films are another way of depicting a story, and again there are pros and cons. At the heart of it is presentation: a movie is, from a viewer’s perspective, contained within a screen. The viewer can see only what the camera does – that is, what is onscreen – just as a reader only sees what an author wishes them to. Hiding characters or acts off screen is an excellent way of manipulating the viewer’s experience since it forces the viewer to use their imagination, which will in turn be influenced by what they have been allowed to see.

Films can make you jump as well. A sudden entrance or quick scene change can have viewers leaping from their seats in a way books can’t quite manage. And filmmakers can show multiple things on a screen at once, while a book must tackle simultaneous actions one by one. That said, I think the cornerstone of film as an artistic medium is the acting. Rather than simply being told in words that “Neil is excited”, we can watch him onscreen and see for ourselves what he’s feeling. An excellent actor can bring believability and depth to a role, and communicate multiple degrees of emotions in a way that is very hard to depict using words. It’s easier to understand the actions of a fellow human than it is to translate words into meaning.

Cinematic limits

Then again, other factors constrain film. Filmmakers usually strive to make their pictures concise and pacey, and often strip away superfluous plot strands and character conflicts in order to streamline the movie. I think this suits films more than books; a film is generally limited to around two hours, and cramming too much into this time can lead to confused plots (and viewers), inconsistent pacing and muddled themes. It’s usually better to have an articulate if simpler film than a clever but convoluted one. Books play the long game though; you aren’t forced to finish one in two hours or even in one sitting. They can take the time to build up a layered story with complex characters and criss-crossing plot strands. Not enough time to read a book? No worries. It might even be trimmed, twisted and turned into a film someday.

Mediums of fiction

Ultimately, storytellers will create stories within the medium they feel most comfortable using. Shakespeare wrote plays, the Beatles wrote music, Kubrick made films. Rush wrote Red Barchetta as a song because they are musicians; if an aspiring author had had the idea first, they may have immortalised it in a short story instead.

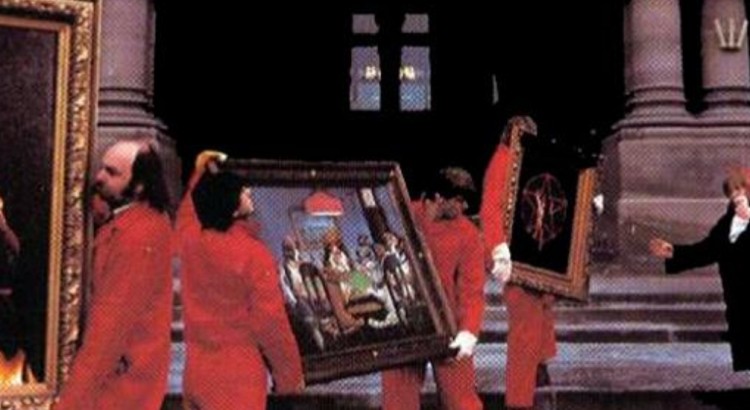

Different mediums allow us different glimpses into fictional worlds. Look at The War of the Worlds. H G Wells wrote a somewhat dry if engaging account of an alien invasion that has since been reinterpreted as a futuristic rock opera, a downbeat action film and even a stage show. But it most most famously adapted as a radio play broadcast in 1938. Listeners were convinced the events in the play were real; legend has it that panic filled the streets.

Different mediums can even influence each other: films like The Crow and Sin City are stylised to show their origins as graphic novels with visually stunning results, and movies are sometimes adapted into novels in order to expand on settings and characters. Even within the format of writing there are many ways of presenting stories using words – prose and poetry, novellas and novelettes, plays and articles… A story will be informed and changed by its medium, and in the best case, enriched by it. I myself have written stories as prose and poems. Can’t decide on one? Try writing a song…

Interesting. I can relate this to learning pedagogy where the general principle is that the more of student’s senses that are stimulated during training (visual, audio, kinetic), the more effective is the learning experience. Is Red Barchetta better watched being played on a live concert DVD when both visual and audio senses are being used? Or when tapping along with drumsticks (kinetic)? Food for thought!

I think it would be worth watching the live concert DVD to test out this theory. You might also want to consider a glass or two of wine with it to replicate the intoxication of watching live music and see where your investigations take you!